Tuesday, 23 October 1962

At 3:00 p.m. in Moscow (8:00 a.m. in Washington – twelve hours after the Soviets learned of the quarantine plan from Ambassador Kohler), on the 23rd, Ambassador Kohler met with Soviet Foreign Minister Kuznetsov who relayed the response from Chairman Khrushchev to President Kennedy.49 At 11:05 a.m. in Washington, President Kennedy received the letter from Chairman Khrushchev via State Department Telegram. In his letter, Khrushchev accused the United States of threatening the peace, violating the UN Charter, piracy, and aggression against both Cuba and the Soviet Union. Khrushchev adamantly declared that “the armaments which are in Cuba, regardless of the classification to which they may belong, are intended solely for defensive purposes in order to secure the Republic of Cuba against the attack of an aggressor.” Khrushchev called on the US to “display wisdom and renounce the actions pursued [by the US], which may lead to catastrophic consequences for world peace.”50

intended solely for defensive purposes in order to secure the Republic of Cuba against the attack of an aggressor.” Khrushchev called on the US to “display wisdom and renounce the actions pursued [by the US], which may lead to catastrophic consequences for world peace.”50

Khrushchev offered the Soviet case back to Kennedy: the weapons were defensive and would not be necessary if the United States stopped its aggressive actions toward Cuba. The “defensive” weapons argument possessed a logical weakness, but frames the clear intent: Leave Cuba alone.

Khrushchev also sent a letter to Castro reaffirming his support to Cuban defenses. He did not, however, inform Castro that some shipments bound for Cuba would be returned to Russia.51

This letter was followed by an interview with Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro affirming that the weapons were of a defensive nature because Cuba never harbored any aggressive intentions against anyone… We shall never change this policy. We shall never be aggressors. That is why our weapons will never be of the offensive type.” Castro went further to declare, “We decidedly reject any attempt at supervision, any attempt at inspection of our country. Our country will not be subjected to inspection from any quarter… Anyone who tries to come and inspect Cuba must know that he will have to come equipped for war. That is our final answer to illusions and proposals for carrying out inspections on our territory.52

The same day, Castro mobilized the entire armed forces of Cuba and Kennedy signed Executive Order 11058 “ordering persons and units in the Ready Reserve to Active Duty” and suspending service separations.53

Kennedy responded to Khrushchev with a letter on the evening of 23 October expressing the hope that “we both show prudence and do nothing to allow events to make this situation more difficult to control than it already is.” He announced that the OAS approved the quarantine and informed Khrushchev the quarantine would be in effect as of 2:00 p.m. Greenwich time (10:00 a.m. in Washington and 5:00 p.m. in Moscow) on the 24 October and stressed to him that “I hope you will issue immediately the necessary instructions to your ships to observe the terms of the quarantine…”54

In their opening letters, both the United States and the Soviet Union agreed that they did not desire war. Both sides wanted all parties to show prudence to ensure that nothing happened to cause the situation to worsen. The United States kept its options open, primarily military, if the Soviets “continued” to lie. The Soviets stalled for time to develop options to seek the most gain or least loss from this situation.

During the day on the 23rd, the OAS and the UNSC met separately to discuss the crisis. Secretary Rusk spoke convincingly at the OAS continuing the unified information campaign waged by the United States. Rusk cited “incontrovertible evidence,” past deceitful statements by Soviet officials, the offensive character of the weapons now in Cuba, the Soviet contribution to the “enslavement of the Cuban people… to which the Castro regime has surrendered the Cuban national heritage,” and Soviet intervention in the Western Hemisphere. The address called for support to establish a “strict quarantine to prevent further offensive military equipment from reaching Cuba” and Rusk submitted a resolution convoking the “Organ of Consultation” and one calling for the removal of offensive weapons. The speech also highlighted the action occurring at the UNSC and claimed that the OAS had the independent right to act to this hemispheric threat to stability.55

The resolutions passed unanimously.56

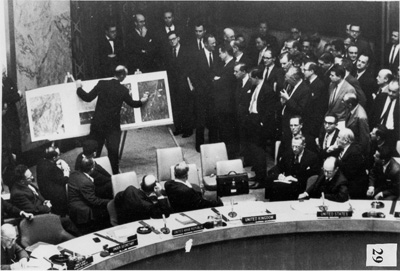

Also on the morning of the 23rd, Ambassador Stevenson released a statement to the UNSC calling for an emergency meeting of the Security Council to address the crisis at hand. This message continued the information campaign and elaborated on the presentation by President Kennedy the night before. He highlighted the domineering spirit of the Soviets citing the Russian advances immediately after the Second World War and calling for a peaceful return to the status quo ante highlighting the American patience and dialog in response to “Soviet expansionism.” He further identified the plight of the Cuban people under Castro as one that betrayed the revolution’s goal of freedom in Cuba. Stevenson focused his comments on the need to remove Soviet influence and withdraw the weapons that the Soviet Union has placed in Cuba. He concluded by submitting his resolution to that end and announced the decision of the OAS.57

Again the United States’ case was pled clearly and uniformly, relying heavily on evidence and fact supported by rhetoric to gain the international community’s support and thus legitimize the quarantine operation.

At the UNSC Ambassador Garcia Inchaustegui railed at length against the American imperialism and  historic threat to the people of Cuba but quoted the Cuban President Dorticas “Were the United States able to give Cuba effective guarantees and satisfactory proof concerning the integrity of Cuban territory, and were it to cease its subversive and counter-revolutionary activities against our people, then Cuba would not have to strengthen its defences (sic)… Were the United States able to give us proof, by word and deed, that it would not carry out aggression against our country, then, we declare solemnly before your here and now, our weapons would be unnecessary and our army redundant.” Ambassador Garcia Inchaustegui, however returned to his strongly anti-American rhetoric citing American piracy, airspace violations, and asserted that American “aggressions” are a threat to Cuba. He continued to claim that Cuba was acting only in its defense against aggressors and repeated Castro’s assertion that UN observers would not be allowed in Cuba.58

historic threat to the people of Cuba but quoted the Cuban President Dorticas “Were the United States able to give Cuba effective guarantees and satisfactory proof concerning the integrity of Cuban territory, and were it to cease its subversive and counter-revolutionary activities against our people, then Cuba would not have to strengthen its defences (sic)… Were the United States able to give us proof, by word and deed, that it would not carry out aggression against our country, then, we declare solemnly before your here and now, our weapons would be unnecessary and our army redundant.” Ambassador Garcia Inchaustegui, however returned to his strongly anti-American rhetoric citing American piracy, airspace violations, and asserted that American “aggressions” are a threat to Cuba. He continued to claim that Cuba was acting only in its defense against aggressors and repeated Castro’s assertion that UN observers would not be allowed in Cuba.58

The Cuban case, in contrast to the United States’, was highly rhetorical and emotional. While the Cubans claimed to be open to negotiations, their case relied on the emotional aspects of United States’ aggression against Cuban Communism to frame its argument. This did not represent a denial of the United States’ claim that Cuba has Soviet nuclear missiles; it only offered as its rebuttal a side-stepping of the issue.

Ambassador Zorin responded with charges citing the Monroe Doctrine, American “Bick Stick” diplomacy, and other American incursions into Latin American affairs. He charged the United States with “aggressive acts… against the small Cuban State” accusing the United States of “naked” imperialism… creating this international crisis, forcing the Soviet Union to call upon the UNSC to investigate this act of war.” At the conclusion of his speech, he submitted a resolution to the UNSC condemning the United States’ action, insisting that the blockade be lifted, proposing that that United States cease interference in Cuban affairs, and calling a summit be called between the Americans, Cubans, and Soviets.59

The Soviet case led with an emotional and rhetorical argument that also failed to deny the United States’ claim and only offered the same side-step regarding American aggression towards a Communist nation. This diluted the strength of the Soviet claims.

As the international community formally discussed the Cuban crisis, other principals were continuing to seek avenues for solution. Robert Kennedy met with Ambassador Dobrynin at his office at the Soviet Embassy in Washington. In the emotional meeting, Kennedy stressed that the deception caused serious harm to the relationship between the President and the Chairman. Dobrynin convinced Kennedy that he was not fully aware of the weapons in Cuba during his earlier meeting with the President. Unfortunately, the meeting didn’t open any specific solutions, but it did establish a tentative bridge of communications and possibly restored some faith in the word of the Ambassador. The Attorney General conveyed a very important message as he departed the Ambassador’s office, “I don’t know how all this will end, but we intend to stop your ships.”60

The diplomatic stage was set. Kennedy opened a back-channel communication route to ensure that his message to Khrushchev got through. That also allowed more face-saving flexibility on the international scene, and enabled a more fruitful agreement behind the scenes to avert war.

The Joint Chiefs issued instructions to go to DEFCON 3 at 7:00 p.m. on 22 October61 and outlined the procedures to for “visit, search, diversion, and taking into custody” ships entering into the quarantine area stressing maximum use of communications and minimum use of force, but stipulating that “if boarding meets with organized resestance (sic), the ship will be destroyed… If it becomes necessary to destroy a ship, ample warning should be given to intentions in order to permit sufficient time for debarkation of the passengers and crew.”62

Donald Wilson reported to President Kennedy that the USIA, using the VOA, broadcast the speech in Spanish over nine stations. Further, he reported that VOA had been completely jammed in Moscow. The stations re-broadcasted the speech every hour and on the 23rd carried the speech by Ambassador Stevenson live from the United Nations.63

The first substantial progress towards a solution began with a phone call from Daily News correspondent Frank Holeman to Georgi Bolshakov. When the two met, Holeman relayed a message from someone in the Department of Justice indicating that “Robert Kennedy and his people believed… that the missiles in Cuba were the Soviet Union’s way of responding to US Jupiter missiles in Turkey.” This was the first potentially semi-official link between the two items. Bolshakov reported to Moscow, “In connection with this [assumption about Soviet motives] Robert Kennedy and his circle consider is possible to discuss the following trade: The US would liquidate its missile bases in Turkey and Italy, and the USSR would do the same in Cuba.” Bolshakov noted, “The conditions of such a trade can be discussed only in a time of quiet and not when there is the threat of war.” According to Fursenko and Naftali, “inexplicably, the GRU station decided to sit on this information from Holeman”64

Also that day a friend of the Kennedys’ Charles Bartlett, met with Bolshakov to discuss solutions, yielding little result. Robert Kennedy then supplied Bartlett with photos of the missiles and asked him to meet with Bolshakov again that day. When confronted with the evidence, Bolshakov was able to convince the GRU Rezident in Washington to forward the message from Holeman to Moscow.65

The advantage the United States held with its days of preparation were clear. The international information campaign established the United States’ case to the international community in less than twenty-four hours from the start of the public phase of the crisis. The Soviet and Cuban diplomats, on the other hand, were presented with the problem on the 22nd and a quarantine on the 23rd accompanied by an unprecedented, unanimous resolution from the OAS on the same day. The pressures of time now were much more compressed with the Americans holding the initiative and the advantage of a unified and consolidated plan.